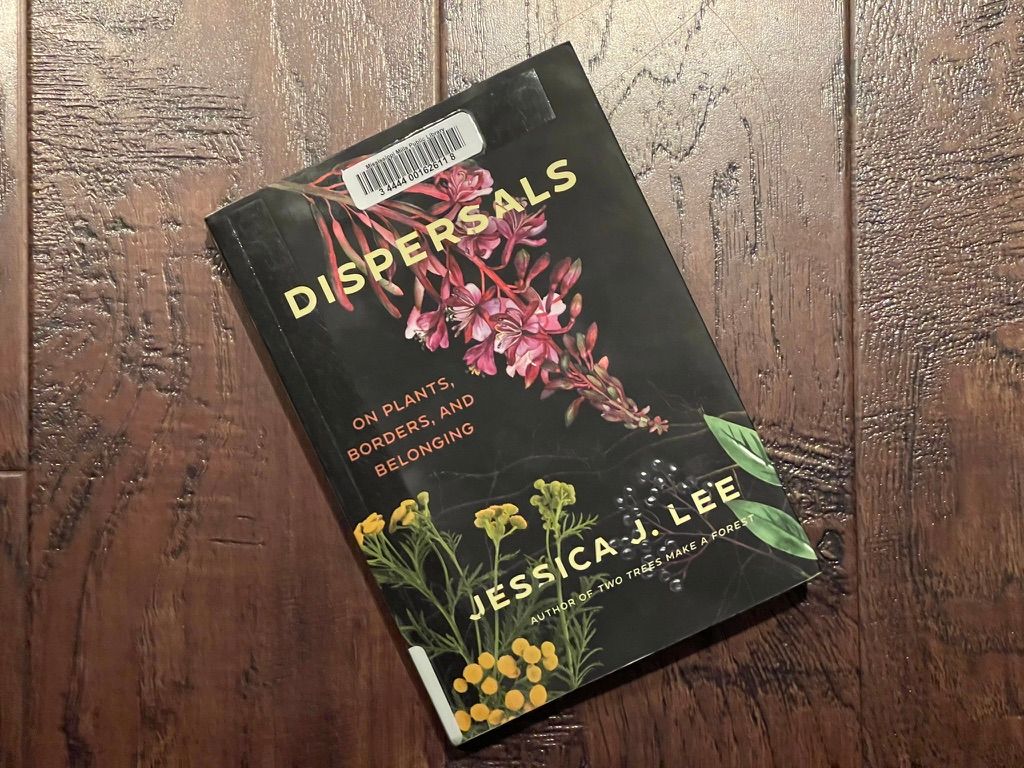

Dispersals by Jessica J. Lee

This is a non-fiction book, but it reads like fiction. The writing is dense in its historical and biological precision, but remains light through the personal narrative that weaved the chapters together.

I loved the parallels the author draws between plant and human histories, for these new connections brought me new perspectives, or mental models, to view my experiences through.

But these questions are not new: that even nineteenth-century texts on plant introductions highlight the anthropogenic forces that shape such plants' movements, I think, forces us to interrogate where and when, exactly, we might locate a version of nature to which we would like to return. At what point do we decide an intervention in the natural world is acceptable? 112-113

In the very first chapters, Lee defines the ideas or borders and margins through patterns plant migration patterns, and highlights how these plant movements are intrinsically intertwined with anthropogenic movements. I found this link between the natural environment and our human experience very powerful, for it forces a shift from humans as being thrown onto a natural world to humans coevolving with it, and calls to reflect about not only about our affect on the world, but the affect of a future world on us, a world that has been affected by us.

Personally, I was taken with the chapters on tea, and pines; but the book is full of gems, each chapter bringing a perspective and lesson.

So I may not think of soil when I think of seed banks—but I do think of the past, and the future that the past makes possible. Perhaps a seed's time is not as linear as I imagine it to be. 184

One one hand, these are histories told through plants, but it also narrative about humans conceptualizing what history is.

I write that when we speak of conservation, it is essential to ask exactly which vision of a place we are conserving. Which means doing history. 217

This also touches on the idea of beauty, and how it is influenced by the empire that defined its meaning.

And I tell him of my love for heather. I have never told anyone about this. I tell him that I want this love to be neutral and easy. But it's bound up with my questions about beauty, how England takes up space in the cultural imagination even if you aren't from here. Underneath, I know the discomfort our conversation points towards: words like "migrant," like "colony." At the crest of the hills, the bus jolts to a stop and we disembark. 223

The book left me so much to think about, but also left me very inspired in a way I can't quite capture.

At the end of our visit, he tells me he'll stay for the day to write, feeling inspired again. And I feel it, too. Something between longing for a place and a longing to write: I feel it now so rarely. 224